With us, smart farming is part of everyday life.

Digital solutions for farm management, fleet management and precision farming: Get to know our farm management applications in the new CLAAS connect!

Your partner for farm management

365FarmNet offers comprehensive solutions for farm management: Since October 2024, our innovative applications are available in the new CLAAS connect across more than 30 countries worldwide — covering everything from operations management to fleet management and precision farming.

If you are already using 365FarmNet, you can continue to work as usual. Our customer service team will, of course, still be at your disposal. Please note that new registrations for 365FarmNet are no longer possible.

Join us in the future of connected farm management with CLAAS connect and benefit from innovative technologies for your operation.

365FarmNet in CLAAS connect

Our farm management solutions have excelled in practice, assisting our clients daily in their tasks. Drawing on our years of experience in agricultural software development and valuable practical feedback, we have co-developed the new CLAAS connect.

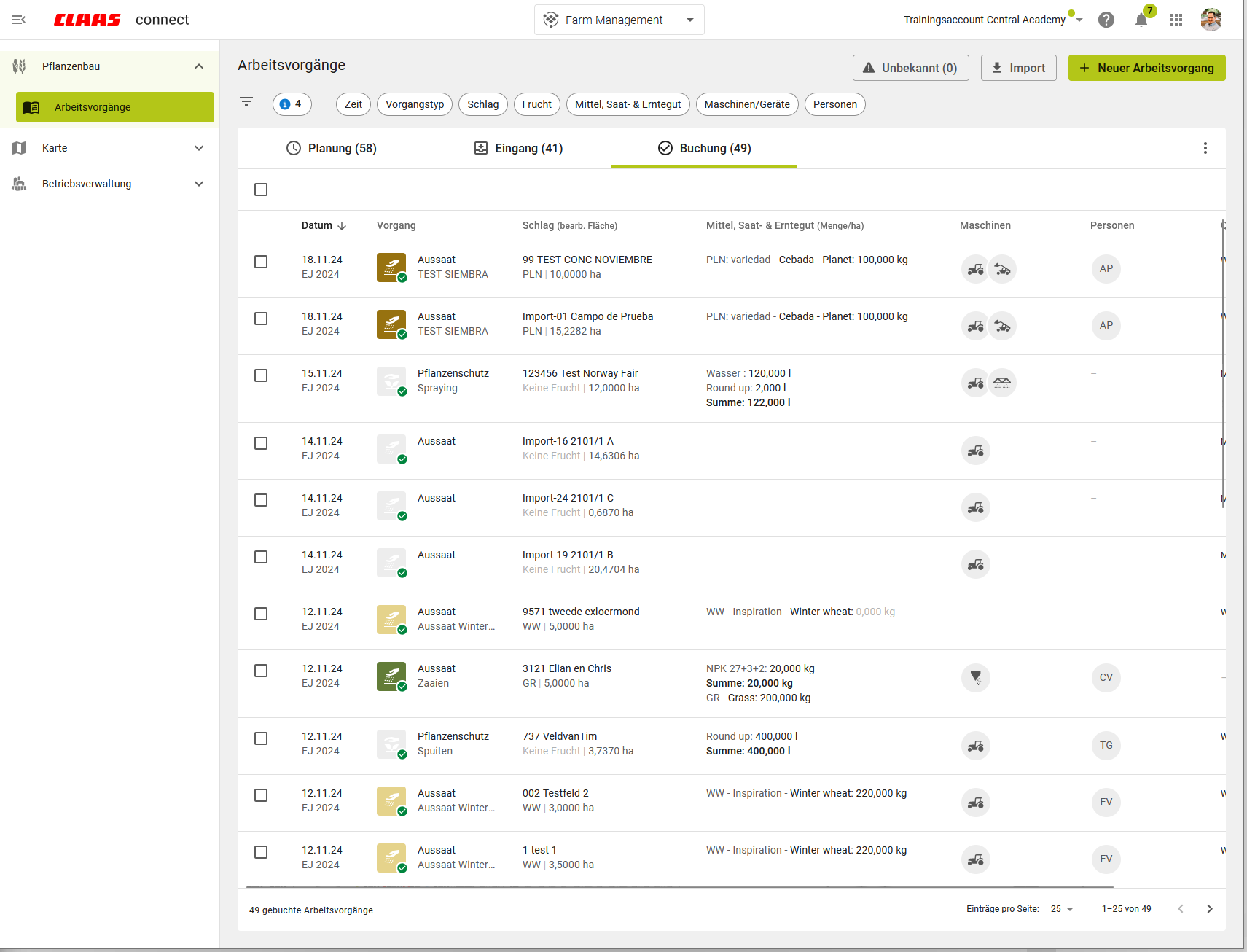

Task management: Proven solution redesigned

In the tradition of preserving and developing good things, we have designed task management in the new CLAAS connect.

Discover the advantages:

- More information in the task overview

- Improved filter functions

- New dialogue for integrating unknown master data

- New: Direct jump from the task to the geocenter for further processing of field data

- New: View additional counter values for all imported data in your files

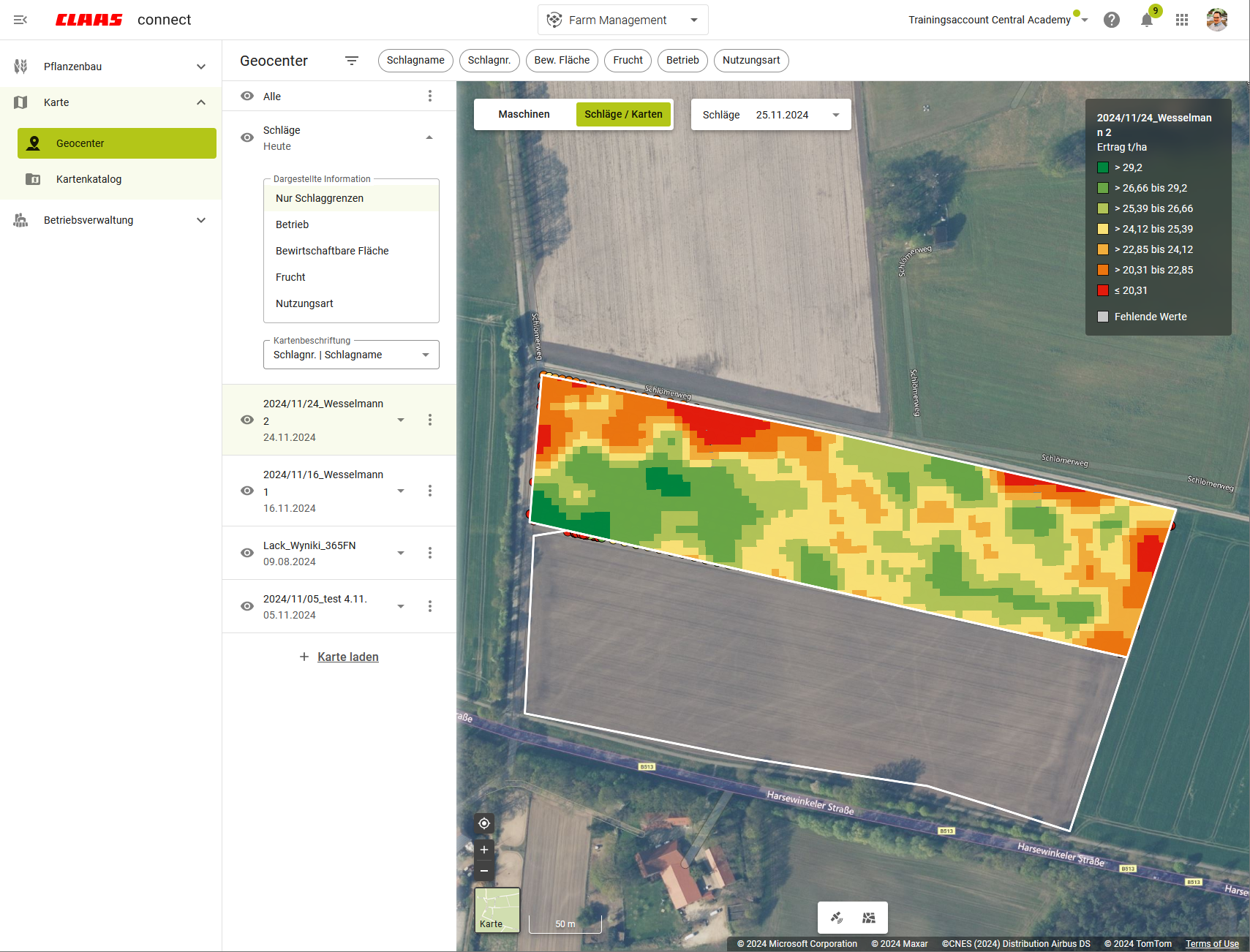

Precision Farming with the Geocenter

With the new CLAAS connect, agricultural businesses in over 30 countries benefit from our updated and expanded precision farming applications. CLAAS connect provides a central “toolbox” through the Geocenter for everything related to:

- Area and satellite data,

- Yield maps,

- Soil samples,

- Machine positions,

- Creating potential and application maps.

From the office to the equipment: Route planning and easy data transfer.

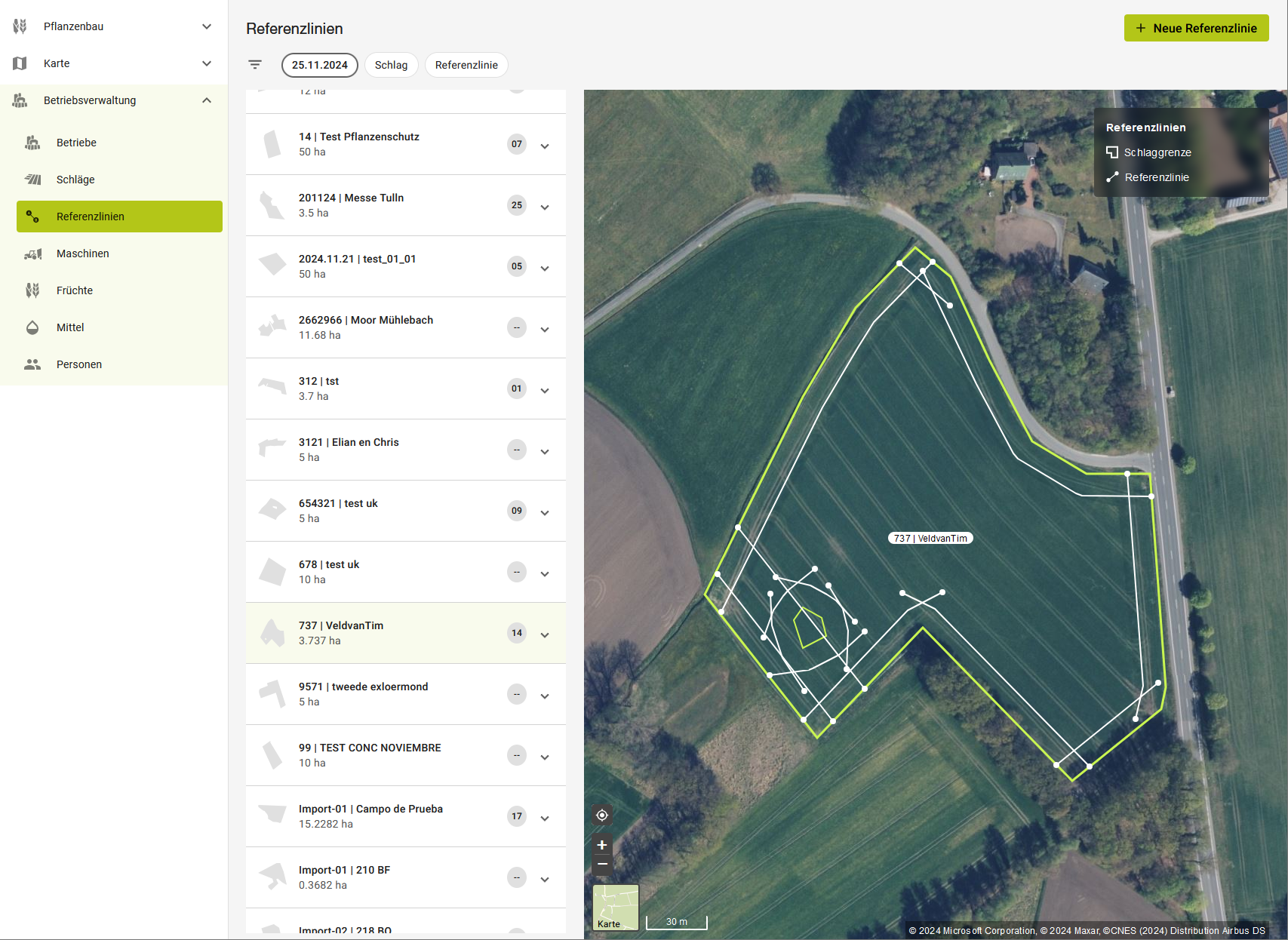

The new CLAAS connect takes route management and planning to a new level. All functionalities are now combined in one seamless application. Your planned routes are automatically integrated into the planned tasks and can be exported directly to your CEMIS 1200 if required.

Route management is available in the Farm Management section of the new CLAAS connect:

- Overview of all reference lines with and without field reference

- New: Quick view of the assigned machine, working width and turning radius

- Editing and duplication of reference lines

- Renaming of reference lines

- Assignment to a field

- Exporting and deleting a reference line

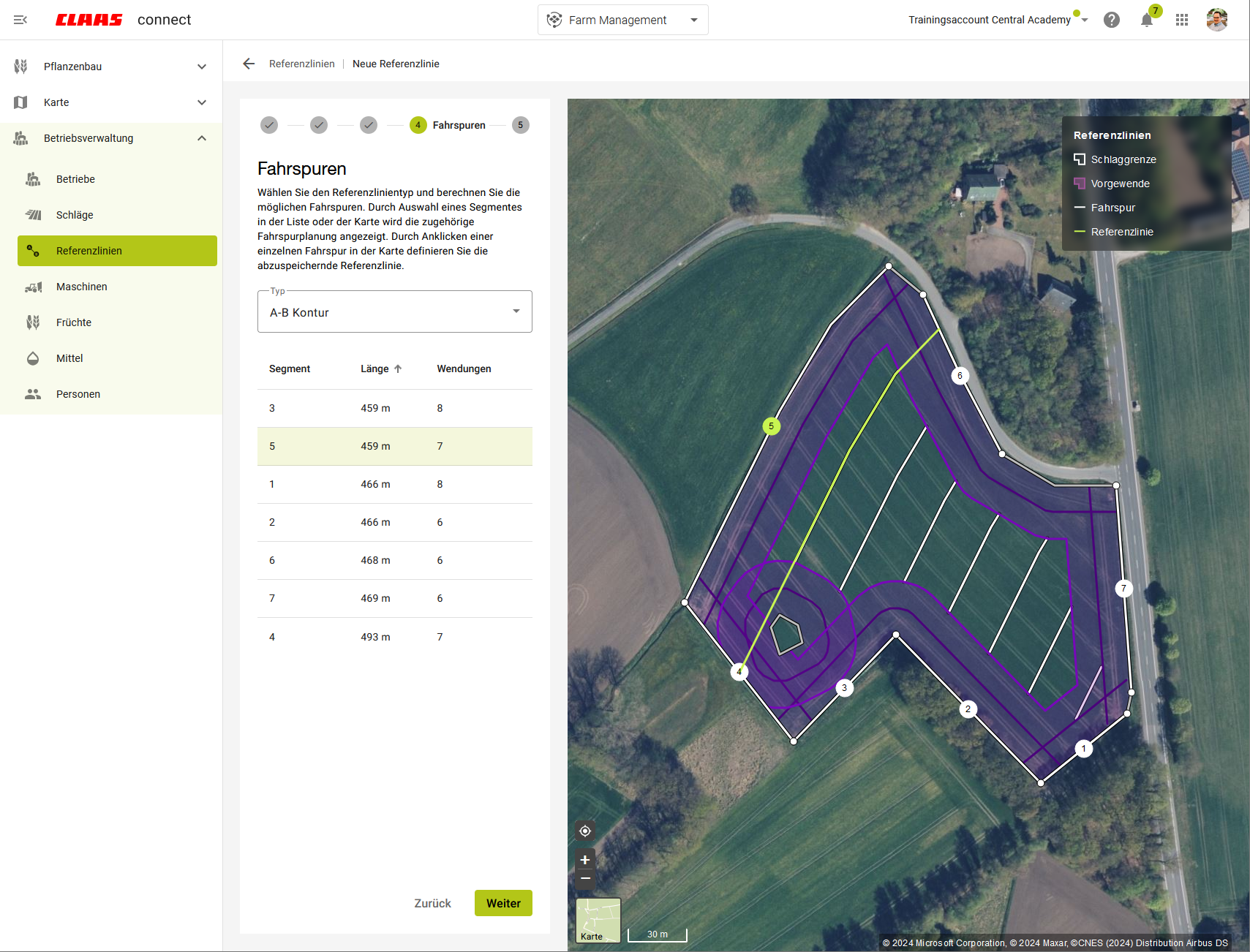

To facilitate seamless usage of reference lines, the creation is embedded directly within the reference line management:

- Selecting the machine performing the task for direct assignment when sending the order to a machine

- Considering the working width and turning radius

- Including headland lines in the planning

- Adjusting lines to the right and left

- Rotating lines at an angle to the right and left

Many new features support you every day.

Experience seamless integration from task planning to application maps, or from the map catalog to task execution. The continuous functions and high performance of the new CLAAS connect make managing and processing your data even easier now.

Discover the new CLAAS connect – Farm Management App – your comprehensive tool for all farm management functions, now conveniently combined in one place.

New features await you:

- Work progress display for CLAAS harvesting machines to estimate processing time

- Task management within the app towards CEMIS 1200

- Create markers on the map and synchronise them with all app users, e.g. field entrances or gully covers

- Send documentation as a PDF via email

- Processing of machine orders.